Tulip Madness: What Three Wild Years in 17th Century Holland Can Teach Us About Cryptocurrencies and NFTs

Monday, 20th September 2021The mid- to late-1630s was a time of unimaginable upheaval. Climate change was a serious problem, with the “Little Ice Age” causing average temperatures to decline year on year, giving rise to crop failures, famine and much apocalyptic pamphleteering. Plague raged in China. Religiously-fuelled conflict convulsed Europe. In Britain, relations between England and Scotland deteriorated to the point of open rebellion. Furthermore, a succession of gaffes by senior members of the Royal Family ratcheted tensions up even tighter.

Meanwhile, the Dutch Republic – which had already created the world’s first stock exchange and stock market – was becoming obsessed with tulips, in particular “broken” tulips – flowers whose petals are not solid blocks of colour but which are fractured into marbled effects. We now know this effect is created by a virus, but in the 1600s how one propagated “broken” tulips was a mystery.

Tulips took time to propagate and bulbs could only be physically traded between June and September. An off-exchange network of tulip futures dealers based in taverns rapidly developed. By November 1636 single bulbs were changing hands for the amount it would cost to buy a big house in the fashionable quarter of Amsterdam. Futures contracts were sold on multiple times in one day. No-one saw the tulips themselves.

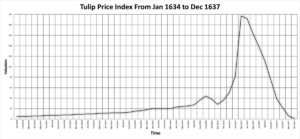

In early February 1637, the market collapsed overnight (see graph). A decree of the Dutch Parliament two weeks later converted all futures contracts for tulip bulbs entered into between 30 November 1636 and February 1637 as options contracts only. Probably suspicion such a measure was on the cards may have had its hand in driving up prices over the winter, with cynical investors knowing a hedge was coming.

Ever since, the tulip mania has been cited as the earliest modern “asset bubble”. How far does it provide lessons to people seeking to deal in crypto-currencies, NFTs or other new financial assets?

A former president of the Dutch Central bank once quipped that – unlike with bitcoin — back in the 1630s one got a flower at the end of the process. Certainly the sailor who in 1636 peeled a 1000 guilder* tulip bulb thinking it was an onion and the Welsh IT developer who in 2013 sent an old hard drive to landfill before realising it contained 7500 bitcoin and his blockchain key probably have a unique understanding of each other’s pain.

More to the point, the tulip mania, while it started among the most sophisticated merchants of the most sophisticated trading nation in Europe, dragged in the 17th century equivalent of the “hobby” traders; people betting their shirts on the tulip markets rising indefinitely. Furthermore, it was market regulation and the prospect of such regulation which both fuelled and shut down the tulip bubble. While the total number of people ruined by the tulip mania may be open to speculation, the truth is that the amateur, ill-informed and underfunded investor suffered disproportionately when that happened.

The same is true of crypto assets. Regulation is coming; the anonymity which once gave them their biggest charm is that which causes most suspicion among financial institutions and regulators worried about dark money.

When it comes, though, it will chill the crypto markets with a chill as cold as the East wind sweeping across the Netherlands on an early February day in the midst of the Little ice Age.

Susan Hall

Clarke Willmott